Should potential egg donors worry about potential dangers?

For anyone undergoing any kind of medical treatment, it’s always weighing the benefits of treatment (will this save my life? Cure my illness?) versus potential side effects (can I endure, say, the headaches or whatever comes with the drug?).

For women undergoing fertility treatments, there’s been a push in recent years to minimize the amount of hormones and the amount of cycles—that will lower any potential risks of drugs and also plummet the cost. (The drugs can costs hundreds of dollars).

The whole risk-benefit ratio is different when it comes to young women who are egg donors. The upshot isn’t making a family but making money. The downside is unknown. The sperm and egg industry have long been unregulated fields.

In today’s New York Times, Jane Brody writes about Jessica Grace Wing, a Stanford undergraduate who served as an egg donor three times. Then she got colon cancer and died at the age of 31. There is no proof that the hormones she took to make her spew lots of eggs in one cycle caused her colon cancer. But there aren’t studies proving the safety.

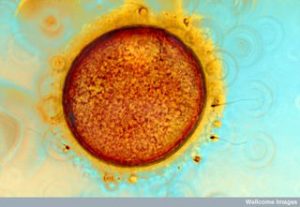

And that’s the issue. Wing was the perfect egg-donor-candidate. She went to a top college, was pretty, athletic, thin, and musical. The hope is that all of those positive things were tucked into the genes in her egg destined to be passed along to the offspring. The fee for her eggs helped pay for college. Where I teach, I hear my college students laughing about the alluring advertisements in the school newspaper. To them it all seems so silly that their genes (not their hard work,not their home environment) got them into college and into egg-donorable standing. It’s just always seemed crazy to me that this business has fallen more in line with the way we deal with any other commodity we want to sell rather than a medical procedure that needs to be tracked for safety.

Her mother, a physician, along with other doctors have been pushing for data bases that can keep track of the donors and their health. This is an idea that has been debated since the egg donor industry started. When I was working on my last book, Get Me Out: A History of Childbirth from the Garden of Eden to the Sperm Bank, I talked to sperm donors and egg donors and the folks who run the businesses. For the most part, the folks “donating” the eggs and sperm (they really sell them), do not want the hassle of the oversight or the bureaucracy of keeping some kind of national data base. The sperm concern isn’t about dangers of donating. Men don’t take hormones. They masturbate in a room. But there are concerns that some men who may be harboring genetic diseases are passing along those illnesses from one bank to another—perhaps unbeknownst to them. The issue for egg donors is their own health. We need to be able to tell these young women—offered thousands of dollars to take heavy doses of hormones that make their bodies release multiple eggs in one month—what the health risks are.

This fear isn’t new. It makes headlines each time there’s a death of a young woman. Today is was a New York Times piece. Two years ago, it was a New York Post piece that showed the photograph of a beautiful young egg-donor who got terminal cancer and had a starring role in a documentary, Eggsploitation. In this day and age, when data is easy to collect and analyze, it’s a shame that we are collecting all kinds of data on what brands of toilet paper people like and who is likely to buy this hat versus that coat, but we can’t collect and monitor data from women who may be risking their lives to help other women make babies.

References

Zarek SM1, Muasher, “Mild/minimal stimulation for in vitro fertilization: an old idea that needs to be revisited,” SJ.Fertil Steril. 2011 Jun 30;95(8):2449-55. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.04.041. Epub 2011 May 7.