When my dog deteriorated to the same level as my father (not able to move or eat on his own and appeared to have little cognitive functioning), I knew it was time to put Dexter, our 13-and-a-half year German Shepherd down.

Dexter hadn’t walked the length of a block in about six months despite twice daily painkillers and a host of other pills to get him moving.

When I arrived at the hospital to end it all, two technicians lifted Dexter onto a gurney and into an examining room. As I wrapped my arms around him—wishing he would close his eyes—the vet, held the syringe of euthanol, and asked: “Are you sure you are ready?”

That was probably the toughest moment of all.

Then she injected him. One huge syringe of a milky-white powerful sedative followed by another syringe filled with phenobarbital that stopped his heart. There was no last cry or yelp. He just dropped his head and peacefully left.

Right away, my dog’s life flashed before my eyes. I pictured him as an 8-week-old puppy with huge floppy ears and then as a rambunctious hulking 5-year-old. That’s when I knew, hard as it was, that we made the right decision.

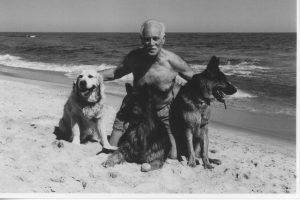

Then, oddly enough, my dad’s life flashed before my eyes. The man he was before Alzheimer’s struck. When he was chairing a world-renowned pathology department, editing a prominent cancer journal, leading the American Cancer Society, running miles every day, lifting weights, and so on.

My dad was always a good listener and a great decision-maker. I could tell him anything and he seemed to simplify the process, ask key questions that allowed me to come up with “my own” solution. Even now, when I visit him in the Alzheimer’s ward of the assisted living home, I tell him things just the way I used to. Sometimes it’s the teenage me, asking for life advice about whether I should do this or that. Sometimes, it’s kindergarten me, “hey, dad. Look. I wrote a book!” Often it’s proud-mom me, “the boys are playing football, just like you did.” And somehow, I just know what he’d say. I’ve even learned to predict those key questions guiding my decision-making process. And I know that if he could talk even for a moment, he’d beg us to end it all.

For years, I’ve been a huge proponent of death with dignity, insisting that surely, we must “do something” for dad. I’m proud New Jersey, where I grew up, may become the third state to allow near-death patients to self-administer life-ending medication. Still, I think for all my talk, I’m just going to have to wait this one out. I really wish we could respect my father’s wishes. We’ve agreed that we will not be reaching for lifesaving remedies should he take a turn for the worse. And yet, if my father’s doctor asked, the way my dog’s vet had: “Are you sure you are ready now?”

I’m not sure what I’d say.