For those of who read the New York Times “Modern Love,” column, we know that every now and then, there’s one that resonates but not because of a shared experience. In fact, it’s just the opposite. It rings so close to the heart because we may not have shared the journey but we shared the emotions.

That’s how I felt when I read Laurie Frankel’s essay last fall about her six- year-old son transitioning from identifying as male to female. She wrote so honestly about wanting to cater both to her son’s happiness but also wanting to protect him from the potentially harsh ramifications, potential bullying.

As a mother of four children, I know there are the abstract conversations (“this is what I would do, if…” ) as we role-play perfect parenting. And then there’s the reality of what we do when we are in the thick of it, when we say the wrong thing, when we are not sure what to do to help our kids immediately making sure it’s best for the long term.

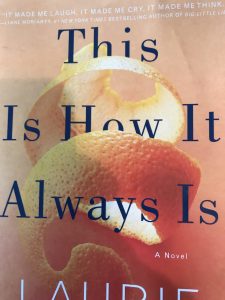

I read Frankel’s essay and was so impressed with her as a writer and as a parent, that when I read in her byline just released the novel This is How it Always is, I clicked on my Amazon app and got it the next day.

After writing and researching medical and emotional issues of those who identify as transgender for my forthcoming book (digging into historical archives, reading memoirs, scouring a trove of scientific articles, interviewing those who identify as transgender, interviewing parents of children who identify as transgender, along with doctors) I was intrigued to see what a novel would offer that I hadn’t gleaned from non-fiction.

A lot.

Frankel intentionally sets up a situation including a family with five kids. She is the mother of one child. She wanted to make the point that identifying as transgender is one thing that complicates growing up, but it’s certainly not the only thing. The other children have their own adolescent issues, too. She also wanted the family to have to cope with the responses not just by parents and the community but by siblings too.

Midway through the book, the mother expresses her willingness to go along with her child’s wishes to transition but expresses her fears of the hormone medication and concerns about the permanence of it all.

“You think Poppy will be the only kid to feel betrayed by her body when it goes through puberty? All teenagers feel betrayed by their bodies when they go through puberty. You think Poppy will be the only woman to hate the way she looks?…..The drugs, other drugs, yet more drugs, a lifetime of drugs, the surgeries, the stuff that can’t be made whole regardless of surgery, these things are huge. These things are scary. These things are mysteries, unpredictable, uncertain….There are hard decisions she’s not old enough to make. There are decisions that just shouldn’t be made for you by your parents. If she is a girl, if deep inside this is her truth, if she needs this, if she wants this, if she must, if she’s sure, then yes, of course yes, thank God yes, we will support her and help and do all all we can and much we can’t yet but will have to figure out, as we have already , as we do for all of our children…”

I spoke to Frankel recently, and I thought she answered two of my questions so well, I wanted to share her answers rather than paraphrase:

RHE: Why Fiction and not memoir?

LF: You know the nice thing about fiction is that parts of it can be true and taken from your own life, but it doesn’t have to be. My hopes and fears drove this whole book. This is probably true of all novels. Also, we are really lucky to live in a community where it was just an easy supported transition in really every way—school, friends, community. It was exactly the way you would want your kid’s life to go. That would have been a short and boring memoir. I also remain keen to protect my kid’s privacy. Everyone knows it was a very public transition. But ten years from now when, who knows who she will be and what she will want other people to know. That would have been impossible in memoir form.

RHE: How do you think your book relates to all children, not just those who are considering transitioning?

LF: I think my story serves as a metaphor. The child you thought you knew turns out one morning to be someone else. That’s what parenthood is like and that’s what childhood is like. And kids change in ways you very frequently don’t know what do to about. You kind of think, here’s the thing: I obviously still love you but I have to think about what to do about it and I have to do the best I can.

RHE: Your book incorporates stories within stories, including a fairytale, and mothers sharing stories. How does the power of storytelling influence transgender rights?

LF: Everything is about story telling. Everyone is reporting and putting their story out, Snapchatting, instagramming. How do you tell your story well and honestly? I teach a college course in literature and we always start with fairytales. They are so problematic for trans kids, for all kids, because what comes first is the whole story. The transformations are instantaneous and painless and permanent and always forward looking and not backward looking. This isn’t a great model for kids with whom the transformation is everything and protracted. They may want to wipe out everything but their parents have no desire to wipe out the past. I’ve been talking to parents and trans kids about how to honor the past, making it part of the story.

This is How it Always is speaks not only to the transgender community, but to any of us who have questioned who we are and who we want to become.