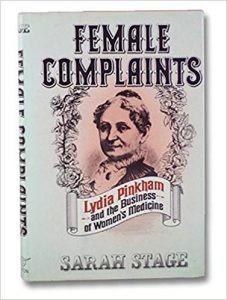

I’m taking a mental health day by avoiding news and immersing myself in medical history. It’s a literary cleanse. I’m reading Sarah Stage’s Female Complaints: Lydia Pinkham and the Business of Women’s Medicine, published by WW. Norton forty years ago, in 1979.

Stage’s book tells the story of Lydia Pinkham’s colossally popular 19th century cure for, well, just about everything. A few sips a day were touted to cure cancer, constipation, menstrual cramps, menopause symptoms, kidney failure and so on and so forth. The target audience was women but men could take it too. The active was alcohol.

Female Complaints delves into the savvy, deceptive marketing.

Remedies that guaranteed cures were all the rage at the turn of the 20th century when lots of people distrusted doctors; when medicine didn’t offer much (this was half a century before antibiotics); when women were embarrassed to talk about female “issues” with their mostly male physicians; when physicians were squeamish to pry into their patients’ womanly complaints.

Not everyone was duped. In the early 1900s, a few muckraking journalists got wind of the false claims such as Lydia Pinkham’s cure and Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup and wrote a series of articles in Ladies Home Journal. (Mrs. Winslow’s Syrup was a mix of morphine-alcohol touted to cure fussy babies that later became known as a baby killer.) Good for Ladies Home Journal. Other media outlets turned down the pieces because of contracts with drug-makers’ advertisers that stipulated the deal would be cancelled if the publication ran anything detrimental to the products. In those days, according to Professor Stage, some $40 million was spent on these kinds of advertising deals.

In part due to these journalists (but mainly due to Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, about the horrid conditions in the meat industry), the Pure Food and Drugs Act was passed in June, 1906 and took effect January 1, 1907. (Opponents claimed the law staunched consumer choice.) The Act stated that medicines involved in interstate trade

- Meet certain standards of purity

- Labels must be truthful

- Toxic ingredients must be listed, such as cocaine, opium, morphine, heroin, alcohol, cannibas. (The label need not list all ingredients.)

While doctors and journalists celebrated their victory and pronounced the so-called fake-medicine business dead, hustlers were strategizing. “In the long run the patent medicine manufacturers proved more astute judges of human nature than the reformers,” wrote Stage.

The truth-law only applied to labels so the quack-medicine peddlers promoted their false claims in signs in streetcars; advertisements in newspapers; and mailed pamphlets.

At the same time, the president of the Proprietary Association, the organization of those who sold these so-called patent medicines, issued a seal to anyone who followed the new rules. “Guaranteed Under the Pure Food and Drug Act.” They knew the sticker implied that the product must be safe and effective. In reality, it just meant that the label accurately stated toxins within. The association assumed, perhaps rightly so, that most people would be convinced by the seal of approval and not read the fine print. (The “guarantee system” was halted in 1914.)

The peddlers also hired “testimonial agents,” who procured upbeat blurbs. One broker charged $75 for a senator’s endorsement; $40 for a Congressman. Women were encouraged to write testimonials and were offered free medicine or the cost of a professional photograph. (They were told letters to Mrs. Pinkham would get replies by the maker, herself. Except for one thing, the deal went long into 1890s and early 1900s, years after Pinkham’s death in 1883.)

Sometimes reading about history soothes my soul because 19th century wackiness takes my mind off of 2019 insanity. Back in my grandparents’ day, consumers fell for slick advertising and testimonials. They were lured by claims that preyed on their fears of aging and promises of quick fixes. Can you imagine if people today were just as gullible?