Fifty-nine years ago this week—on May 9th, 1960, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the birth control pill.

The story of the oral contraceptive is unique among hormone histories. It was the first drug prescribed to healthy people for social reasons—a drug that didn’t prevent a disease or even promote wellbeing. It’s the only pill called The Pill. You can’t say that about any other treatment, not even a headache tablet, a vaccine or an operation. That’s what Dr. Carl Djerassi, a pioneering pill researcher, once boasted.

The idea that hormones can be used to prevent conception was based on something doctors and farmers observed for centuries: You can’t get pregnant when you’re pregnant. But it wasn’t until the early twentieth century that an Austrian physiologist explored the notion.

In 1919, Ludwig Haberlandt, a professor of physiology at the University of Innsbruck, wondered if the pregnancy-infertile idea had something to do with the way ovaries change during pregnancy. He transplanted ovaries from pregnant rats into non-pregnant ones. The recipients could not get pregnant.

Twenty years later, in The New York Herald Tribune, William G. Lennox, a neurologist quipped: “An anti-pregnancy hormone which might help solve the growing problem of the overpopulation of the unfit.” (It was considered one way to promote this controversial notion of preventing conception.)

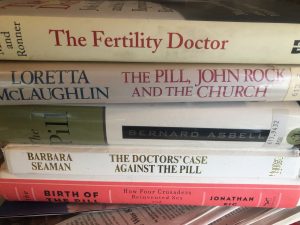

The history of the pill includes maverick scientists—some traipsing through the forests in Mexico for a plant that made an estrogen-like substance. It also includes feminists pushing for a hormone-based contraceptive when even the mention of birth control was considered obscene—not the news fit for print. Jonathan Eig, recounts the story in The Birth of The Pill: How Four Crusaders Reinvented Sex and Launched a Revolution, a page-turner tale for anyone who wants to dig into the history and get to know the personalities behind the discovery and dissemination.

When the FDA green-lit the first pill in 1960, the process was seen as a triumph of science and society, working together for a medical advance. Compared to all the other medical discoveries, hormones had seemed safer. They weren’t made from germs the way antibiotics and vaccines were. They weren’t toxins like many cancer drugs. They mimicked human chemistry. They were a seemingly natural remedy to control the most natural event of all—making babies.

By the 1970s, more than 6.5 million women were on it.

But the birth control pill came to symbolize a turning point in our relationship to hormone therapies. Fears mounted that this hormone contraceptive, in the doses delivered, was triggering headaches, bloating, and also life-threatening blood clots.

Today the pill comes in much lower doses than the original form. We also have package inserts that list all the potential side effects. This is, in part, thanks to such as Barbara Seaman, who wrote The Doctor’s Case Against the Pill, and Alice Wolfson, now a lawyer in San Francisco, who as a 29-year-old interrupted the 1970 Senate hearings to demand that women’s voices be heard.

Yet, despite these huge advances, we could do better. There are still women who feel depressed on the pill. Others who suffer from life-threatening blood clots. Too many women are denied access to affordable contraception. The 59th birthday of the birth control pill should be a time not just to consider the scientific and political feats that made this all possible, but to think deeply about where we are today and what we need to make contraception safer and available for all women who need it.