The Birth of Forceps Offers Insight to Birth Today

There’s an upside to being a snooping guest—you could find a long-lost treasure as this nosey 19th century mother-in-law did.

In 1813, Dr. William Codd’s mother-in-law was poking around he and his wife’s home in Essex, England. She noticed a crack in the floorboard, pried it open, and hoisted a box of metal trinkets. She must have thought the stuff looked scientific because she ran the box over to her friend, a retired surgeon who lived nearby. He knew immediately that she found a medical treasure. One that had been missing for a hundred years.

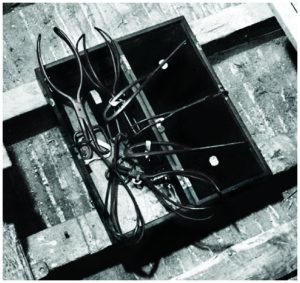

Inside the box were the world’s first usable forceps. They were created in the 1500s by the Chamberlens, passed down from generation to generation until Peter Chamberlen retired and hid them in the floor of his estate.

The story of forceps is one of a huge medical advance. Before forceps, babies stuck in the birth canal died, and sometimes so did the expectant mother. But it’s so much more. It’s a story of fierce competition and bitter debates.

The Chamberlen men developed this lifesaving device and then refused to share the secret because they figured (rightly so) it would give them an edge in the childbirth business. They became the male-midwives to aristocrats and royalty. And to make sure no one stole their idea, they stored the forceps in box the size of a coffin (so there were no clues about its size or shape) and then blindfolded the laboring women so she couldn’t sneak a peak, either. (As if a woman about to deliver a baby is going to grab a pen and paper—or quill and parchment—and jot down notes).

Eventually in the mid 1700s, Peter Chamberlen, a great-great nephew of the inventor, realized he could make money selling the design. So he did so to Dutch and then British doctors. When he retired, he buried the original forceps in the floor of his house. And there they remained until the nosey mother-in-law of the next home’s owner happened upon them.

I was telling the tale of the eccentric Chamberlens this week when I was interviewed on KWMR radio by Christina Lucas, a nurse in Point Reyes, California about the history of childbirth. I thought I knew the story pretty well until she said, “Where are the forceps now?”

I was stumped during the show, but promised I’d do some searching afterwards. Like most things in life, the answer was one Google click away. The forceps are now on display at the museum of the Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists.

Since the Chamberlen days—or really starting with the Chamberlen’s, forceps have instigated some of the most contentious childbirth debates. Women worried about the safety of high-tech birth (forceps) versus natural birth (sans forceps). The concerns are reminiscent of the cesarean section versus no-cesarean section debates today.

Today forceps fit into the natural category and many obstetricians believe that the art of using them (it takes a bit of skill) needs to be re-introduced to minimize the high rates of c-sections. There are also initiatives to teach forceps skills to women in developing countries, where surgical births may not be an option.

In any event, if you’re as curious about childbirth history as I am—and if you happen to be in London—it’s worth a stop at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologist’s museum. You have to make an appointment. The College is near Regent’s Park, a lovely part of town.

And if you’re really curious, you can hop on a train from Liverpool street to Hatfield Peverel in Essex and see the Chamberlen’s former home. It’s called Woodham Mortimer Hall. There’s a blue plaque on the door that rehashes the history in a few sentences. The Hall is now private, but you can see if from the outside and visit the cemetery nearby. (It’s also a lovely area of the English countryside…where I got my first puppy, a Golden Retriever.)

I’m glad that Christina pushed me to get to the end of the mystery. But the one thing we’ll never know is what Dr. Codd said when he got home that afternoon and found his mother-in-law dismantling his flooring.